Image via WikipediaAmericans understand diversification, but not inflation - Articles - Employee Benefit News Surprisingly, most Americans showed understanding of diversification, asset allocation and dollar-cost averaging, while flunking basic questions about other financial concepts in a survey for Northwestern Mutual. This discrepancy is consistent with findings in a 2006 study.

Image via WikipediaAmericans understand diversification, but not inflation - Articles - Employee Benefit News Surprisingly, most Americans showed understanding of diversification, asset allocation and dollar-cost averaging, while flunking basic questions about other financial concepts in a survey for Northwestern Mutual. This discrepancy is consistent with findings in a 2006 study.Thursday, November 18, 2010

Americans understand diversification, but not inflation - Articles - Employee Benefit News

Image via WikipediaAmericans understand diversification, but not inflation - Articles - Employee Benefit News Surprisingly, most Americans showed understanding of diversification, asset allocation and dollar-cost averaging, while flunking basic questions about other financial concepts in a survey for Northwestern Mutual. This discrepancy is consistent with findings in a 2006 study.

Image via WikipediaAmericans understand diversification, but not inflation - Articles - Employee Benefit News Surprisingly, most Americans showed understanding of diversification, asset allocation and dollar-cost averaging, while flunking basic questions about other financial concepts in a survey for Northwestern Mutual. This discrepancy is consistent with findings in a 2006 study.

Labels:

Asset Allocation,

Investment

What to take away, what to trash from the ‘Twinkie Diet’ - Articles - Employee Benefit News

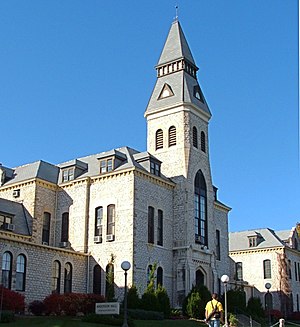

Image via Wikipedia What to take away, what to trash from the ‘Twinkie Diet’ - Articles - Employee Benefit News Mark Haub, a Kansas State University nutrition professor, lost 27 pounds and lowered his cholesterol levels by eating a 10-week diet of mostly Twinkies and Doritos and adding no extra exercise.

Image via Wikipedia What to take away, what to trash from the ‘Twinkie Diet’ - Articles - Employee Benefit News Mark Haub, a Kansas State University nutrition professor, lost 27 pounds and lowered his cholesterol levels by eating a 10-week diet of mostly Twinkies and Doritos and adding no extra exercise.Related articles

- Video: Professor Loses 27 Pounds on Twinkie Diet (shoppingblog.com)

- The Twinkie Diet Poll: So what's your "guilty pleasure?" (pongr.com)

- What's The Craziest Diet You've Ever Been On? (thefrisky.com)

Labels:

Wellness Plans

The Deflation Scenario

You probably worry about inflation-but deflation, too, is a threat you need to understand.

Financial Planning

By David E. Adler

November 1, 2010

…Extremely low inflation can easily tip into deflation, and several economic indicators are flashing red. Most critically, the CPI is dangerously low, at less than 1%. Investor and consumer confidence and demand are at similarly depressing levels. And the overall economy is still deleveraging.Image via WikipediaMost planners keep their eyes on inflation. But the Fed has worries in the opposite direction: Once unthinkable, deflation is now a threat. In September, the Fed's Open Market Committee Meeting found "measures of underlying inflation are currently at levels somewhat below those the Committee judges [optimal]."

That's why some economists can't rule out the possibility of deflation. "I would say there is a fifty-fifty chance of deflation occurring within the next 12 months," says Ibbotson Associates' economist Francisco Torralba.

Image via WikipediaThinking through deflation and its effect on … portfolios-and lives-requires new and possibly unfamiliar approaches, since deflation has been rare since the end of World War II. … The bigger challenge facing advisors is that much of their job is helping people to achieve their dreams. What will happen to these dreams if deflation becomes a reality?

MORE DEBT, FEWER ASSETSDeflation is devastating because people's debts increase in real terms, while the value of their assets, including business inventories, decline. If it tips into a severe spiral, borrowers default, credit becomes impossible to obtain and the wheels of commerce stop spinning. "If the Fed can't stop deflation, we are looking at the possibility of government default," says Jon Ruff, director of research for real assets and strategies at Alliance Bernstein.Ruff puts very low odds on severe deflation happening-less than 6%-and adds that it's highly dependent on whether we see a double-dip recession. But other analysts, citing new academic research, are less optimistic."When the core CPI inflation rate falls below 1.5%, the risk of deflation increases," Torralba says, in part because the Fed can only lower interest rates so far before hitting zero. …

The United States faced similar risks of deflation in 2002, Torralba says. After the dot-com crash and the terrorist attacks of 2001, inflation in the first few months of 2002 barely nudged above 1%. But the economy escaped the threat; economic conditions that year were a far cry from the high unemployment and brutal deleveraging of today.

Consumer expectations about deflation, which can become a self-fulfilling prophecy, are alarming. The 10-year expected inflation rate by consumers, as measured by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, was only 1.54% as of mid September, and that expectation has been declining since 2008.

Finally, there are signs the economy is undergoing a regime shift, where deflation has replaced inflation as the primary threat. The main reason is that the rise in global labor productivity and supply drive down prices on manufactured goods, particularly without a rise in global demand. However, globalization trends also increase price pressures on commodities and other industrial inputs. The picture is far from simple.

Robert Tipp, chief investment strategist for fixed income at Prudential, believes this is the case. The re-emergence of deflationary pressures in the 21st century goes beyond the high unemployment and debt levels of U.S. consumers to encompass other macro factors, principally globalization, according to Tipp. "Deflation is not a likely scenario, but it will crop up on the risk spectrum for years," he says.

DEFLATION PORTFOLIOS

Financial planners searching for insight into how different investments respond to deflation can look to history for guidance. … [The] United States itself offers deflationary parallels, most recently in the 1930s.

Brian Gendreau, market strategist for Financial Network Investment Corp., an RIA based in El Segundo, Calif., says, "I go back to the very slow economy from October 1937 to August 1939. Banks and companies were flush with cash, and deflation was 5%." Gendreau, who is also a finance professor at the University of Florida, notes that during this period equity valuations fell by 36%.

But there were a few bright spots: Stocks that paid high and stable dividends, such as public utilities, did well as investors piled in. During these two years, prices for high-grade corporate bonds and municipals also appreciated. In general, investors sought yield and safety, and they were rewarded for it.

Parallels with the past are not exact, of course. The price of gold, for instance, declined by 1.2% from 1937 through 1939. Although Gendreau does not think deflation is a definite, he does believe that it remains a risk. …

So is it too late to make the bond play Gendreau suggests? If you look at history, he argues, it isn't. Bond yields were already low at the beginning of 1937, but yields continued to decrease (and prices continued to rise) well until 1941, two years after the deflation ended.

A MULTI-FLATION STRATEGY

Planners may be familiar with the idea of deflation and may even be taking steps to hedge against it via large fixed-income or Treasury allocations. … More critically, Ruff argues, the traditional deflation protection offered by Treasuries could be overwhelmed by the possibility of government default that would accompany severe deflation. Even without a true default, the risk alone could depress prices.

… Many analysts believe that despite the immediate concerns about deflation, the greatest long-term threat is still inflation. So in addition to the deflation protection offered by high-quality bonds, portfolios also need hedges against inflation….

"We are in a multi-flationary world; you can't say deflationary or inflationary," says Ben Marks, president and CEO of Marks Group Wealth Management in Minnetonka, Minn. "Instead, you have different headwinds affecting different asset classes." As Marks points out, there is excess supply in housing, commercial real estate and the labor market. As a result, the United States is experiencing deflationary pressures in all three sectors. At the same time, new demand for commodities from emerging economies is creating inflationary pressures. Finally, he doesn't rule out the possibility of stagflation, last seen in the 1970s….

From an investment perspective, Marks is cautious about fixed income. Even though bonds are the natural hedge for deflation, he believes that the market has already priced this in. Instead, he makes carefully selected equity investments in sectors and companies that can survive deflationary pressures.

His focus is on best-of-breed companies that will win market share as rivals go under. Or he looks at firms with unique products and pricing power.

Marks also invests in growth trends, targeting industries that he believes will flourish regardless of deflation or inflation, such as wireless technology. He focuses on companies that have built up an extensive infrastructure, creating high barriers to entry for competitors….

The Depression-era-type portfolios embraced by many planners are one approach to a dark period. But there are dangers in being overly defensive. The economy could revive sooner than advisors and economic forecasters have planned for. "Investors need some selling discipline. The economy will not be weak forever," Gendreau says.

David E. Adler contributes regularly to Financial Planning. His most recent book is Snap Judgment.

Related articles

- Street Smart: Do You Know What Deflation Is? [Video] (dailyfinance.com)

- Inflation? Gary Shilling Says Deflation Is the Real Problem (dailyfinance.com)

- Annual Core Inflation Drops to 0.6%, the Lowest Ever (dailyfinance.com)

Wednesday, November 17, 2010

Why C.E.O.'s Succeed (and Why They Fail): Hunters and Gatherers in the Corporate Life

What are the factors that determine which C. E. O.'s succeed and which fail? Even in the high-tech world, the laws of the jungle still rule.

strategy+business magazine

By Edward F. Tuck and Timothy Earle

{The authors of this article are an early-stage venture seed capitalist and an anthropologist who specializes in leadership.}

… Why do these otherwise successful, competent, well-trained people fail? Why, in the face of good advice, do they do things that bring their ruin? Why, after they fail, can people of less training, skill and intelligence turn their failures into successes?

…We have examined the most common ways that C.E.O.'s fail by applying the findings and techniques of anthropology to business organizations. We have found that the cause of these systematic failures is not the C.E.O.'s lack of skill, nor even his psychology; it is the changing institutional context in which he must perform.

C.E.O.'s fail most often in these three situations:

… Something changes when a company reaches a certain size that makes it somehow different to manage; also, running an independent company is different from running a division of a large company. In short, small-company C.E.O.'s fail in large companies, large-company C.E.O.'s fail in small companies and C.E.O.'s who have risen through the ranks can't work with their boards.

- He or she has moved to a much smaller company, either as an entrepreneur or to take over a start-up or early-stage company;

- The C.E.O.'s small company has grown to middle size;

- The C.E.O. has been a successful vice president or chief operating officer and has been promoted to chief executive, or has been recruited as chief executive for another company.

Camp, Corporation and Community: The View from Anthropology

… In a company, as in any polity, each person behaves according to his or her rules about behavior in groups. …[Half] of them, according to recent research,(1) are inherited. … When we try to succeed in a group, we unconsciously call on those primitive patterns of behavior …; and the structure of our groups comes from the way we behave together.Image via WikipediaEvery company is a polity: a "politically organized community." …[Each] director, officer, manager and employee of a company is a functioning member of the polity.

Anthropologists study people, their cultures and their polities. … When anthropologists find basic similarities across polities with no historical relationship, they believe that these similarities may come from behavior of biologically similar humans adjusting to the same organizational problems.

We have found patterns in these "primitive," isolated human polities that will help C.E.O.'s understand and solve difficulties in their relationships with their boards and their employees. …[Boards] are organizationally different from the corporations to which they are attached. We learned that the founder who is ruined by his company's success, the captain of industry who cannot run a small company and the seasoned executive who cannot be promoted are all victims of the same simple and ancient effect, and we propose a reason for that effect.

First, let's compare organizations.

There are three primitive organizations that have counterparts in modern companies: the working group, the camp and the hierarchy.

The Working Group

When a hierarchical organization like a corporation or an army sets up a working group, a leader is named by the hierarchy ("chairman" or "squad leader"), although the real leader of the group emerges informally. … [Usually], the leader arises without any special action as the work progresses, and leadership passes from one person to another smoothly as the nature of the work changes. … When the problem is solved or abandoned, the group disbands.Image via WikipediaA "working group" is found in all cultures.(2),(3) It is a temporary association of two to six people with useful skills, and it has a specific purpose: to hunt, to lay a section of railroad track, to right an overturned car, to catch a criminal. … They exist only for the purpose at hand, and they are organized quickly and informally.

The result of the group's work has a strong effect on the mood of its members. If the work is successful, they are elated and often celebrate. If the work is a failure, its members are depressed and uncommunicative for a time. Working parties are short-lived, have only a few members and are re-formed as needed.

The Camp

Hunting and gathering "camps" usually comprise about 30 people, from up to six families. The business of the camp -- hunting, gathering, cooking, building -- is done by temporary working groups as defined above. …[Today’s] hunter may be tomorrow's gatherer or hut-builder, although special skills such as stone tool making are recognized by all.

The hunting-gathering camp does not admit to having a leader; in fact, members of the camp will deny there is a leader. They will say, "We're all leaders." Nonetheless, a member of a nearby camp will say, "That's Joe's camp."

The camp thus does have a person who facilitates decisions. He or she does not command, but is respected because of knowledge, judgment and skill in organizing opinion. He or she does not give orders,(4) but focuses the decision-making process. Decision-making in a camp is a political, deliberative, consensual process. The camp's elders are expected to choose courses of action that are acceptable to the camp, and to accept suggestions from everyone. The whole camp behaves in a consensual manner and there is strong social pressure to conform. (In functioning camps, all members are interested in the facts, are fully informed of them, continuously discuss them and are aware of the various alternatives being considered.) …

Where a consensus is not found and distrust and disagreement linger, the usual solution is for the smaller faction to leave, striking off on its own. …The faction that takes off risks its very survival if a new camp receptive to it cannot be found.

When a camp grows to about 50 people, it becomes unstable and splits into two or more camps. This pattern of size-related instability is repeated in organizations of all kinds across human society.

The Hierarchy

The tribe, which may encompass several camp-sized groups, is a hierarchy. Hierarchical organizations have a clearly defined leader, and often many strata of authority. …The tribal hierarchy made it possible for more than 50 people to live and work together, at the cost of personal and group autonomy.

Simple tribes are organized into local groups of a few hundred, each with its own leadership. More complex tribes are organized into regional chiefdoms of several thousands, each with a hierarchy of leaders.

The State

In the archaic world, states eventually evolved to organize much larger populations, often living together in cities and relying on market exchange. It was at this time that real bureaucracies emerged, both to solve efficiently the problems of large groups and to control those groups for the will of dictatorial rulers.

With industrialization and cheap transportation, people began to live together in even larger groups. … At first, these were outright dictatorships, but improvements in communication, education and the economy led to a revision of societal values so that now all members of hierarchical societies have some voice. …

Size Determines Structure

…It appears that six or seven is the largest number of relationships that one person can deal with continuously. We need the hierarchy, with its well-defined roles and patterns of behavior, to allow large numbers of people to work together without overload.

An important study(5) has shown that decision-making performance in egalitarian groups falls off rapidly as the group size grows beyond six. This is a result of a well-studied limitation of the human brain, which cannot simultaneously retain and process more than about seven "information chunks" at once. (One such study by the Bell System set the size of local telephone numbers at seven digits.)

To make larger groups work while still retaining their egalitarian nature, six or seven groups form a "sequential hierarchy." …The largest stable group in which this process has been observed contains about 100 people, and involves three levels of consensus; the usual maximum is about 50 people (7 times 7), and uses two levels of consensus.(6)

Two points to hold in mind are: 1) As group size changes, so must its organizational structure. … 2) Within a single social system, groups of different scale exist and require different organizational structures. A major dysfunction occurs when an organizational structure appropriate for one scale is used for groups of other sizes.

The Camp in the Hierarchy

At the top of every stable hierarchy there is a camp-like consensual group. Even in outright dictatorships there must be an egalitarian council, as Machiavelli advised 500 years ago:

"A prudent prince must ... [choose] for his council wise men ... he must ask them about everything and hear their opinion, and afterwards deliberate by himself and in his own way, and in these councils and with each of these men comport himself so that every one may see that the more freely he speaks, the more he will be acceptable."(7)

The Modern Organization

Thus, four types of organization have arisen when people live together and try to do something in common: the working group, the camp, the general hierarchy and the state bureaucracy.

The most primitive of these is the working group, up to six people. It is also the one that elicits the most profound emotional response. The camp, up to 30 to 50 people, is the next most primitive, and is a very old structure. Camp-like groups are found among non-human primates, and in all human societies.

The most modern organizations, and therefore the ones for which we are by nature least adapted, are the hierarchy and the bureaucracy. Behavior in a tribe, a company or a nation is not innate: it is learned, in contrast to behavior in camps and working groups, much of which is innate. An individual's success in a hierarchy depends on how well he or she has learned its rules, and to what extent his or her innate behavior allows that person to conform to those rules. {emphasis added}

The Modern Corporation

A modern corporation employing more than 100 people is a hierarchy; a company of more than 1,000 is a bureaucracy. A camp-like board of directors is at the top, to offer guidance by diverse experience and to provide intercorporate information. The corporation's best work is done by working groups.

The advantages and satisfactions of recognizing the egalitarian…

How Boards Behave

Since boards are like camps, a successful C.E.O. must remember how camps behave.

A board is not a working party. It cannot solve problems, it can only approve or disapprove courses of action proposed by its leader. If it is forced to choose between alternatives, a crisis of leadership often arises.

The C.E.O.'s leadership role is not openly acknowledged by outside board members, who strongly assert their equality. The C.E.O. thus must reach consensus among board members before proposing important issues. This process is called "keeping in touch."

The C.E.O. is the natural leader of the board. … If the chief executive refuses to lead, then the C.E.O. and board will flounder or another individual member will assume leadership. In either case, the C.E.O. must be replaced. This is because the surrogate leader cannot lead well unless he or she assumes the C.E.O.'s role inside the organization as well as on the board.

Board members expect the C.E.O. to be their leader and will treat him or her as such until they decide to fire the person. … If an act or utterance of the C.E.O. is unreasonable in this leadership context, the other members will believe at a deep level that he or she is incompetent or insane. Since in either of these cases the C.E.O. must be replaced, an extremely unpleasant and difficult task, a member will sometimes opt for denial by assuming that a chief executive who exhibits such behavior is manipulative or evil, either of which is a disquieting but acceptable alternative.

The Ways C.E.O.'s Fail

We can now examine C.E.O. failure modes by comparing modern companies with polities in primitive cultures, and by recognizing that much of our behavior is genetically determined and will be similar when working within groups of the same size. Our understanding of the short-term development of companies can thus be aided by knowing the long-term evolution of human society.

These comparisons confirm anecdotal evidence that successful management techniques are fundamentally different for companies above and below a critical size, and that techniques which succeed in a company above the critical size will fail below it, and vice versa.

The comparisons also explain why C.E.O.'s who are successful as division or subsidiary managers in large companies are unable to run independent companies. These failures are related to their inability to deal with their camp-like boards of directors.

Consider the following scenarios:

Problems With the Board: The New C.E.O.'s Surprise

Those few extraordinary individuals who succeed by climbing to the top of a hierarchy are surprised and sometimes quickly fail when faced with the need to immediately lead the board. …

The result is that the C.E.O. often arrives at his position as head of the board without realizing that his role has fundamentally changed. He assumes that he simply has an organization like his old division or function to command.

If his whole experience has been in hierarchies, he may define himself as one who gives and receives orders… . If he has had no experience with boards of directors, he may make the fatal error of regarding his board as his new boss, as a working group to solve his company's problems or as a part of his organization that he must supervise. If he is told that he must lead the board but not command it, and that he must work by consensus, he finds this incomprehensible. …

If, in fact, the C.E.O. does not lead the board, the board's other members, … are confused and become unruly. The C.E.O. and sometimes the organization itself then fail. …

Problems With Becoming Big: The Faltering Founder

Unless he has access to an enormous amount of money, the founder of a company must first found a camp. In a camp, as we have seen, there is little specialization; in a new company, it is common to hear, "I wear a lot of hats." It is also common to operate by consensus: members marvel at the speed with which decisions are made, and at their feeling of mutual support, clear objectives and clean, unambiguous communication. Employees at all levels speak as though they know what is going on throughout the company. Most of the company's people work far more hours than a normal workday; they enjoy their work.

If the company succeeds, it grows….

The appropriate action is to assemble a hierarchy, using experienced people, when the company's staff numbers more than 20. … The C.E.O. must gradually abandon his role as consensus leader and take on the role of chief.(8)

This is a difficult transition even for C.E.O.'s who understand the problem. Often, a founder has chosen his role because of difficulties in a hierarchy; he sees the transformation of his company to a hierarchy as a personal failure. At best, he must deal with alienation and feelings of betrayal in people with whom he has worked closely, and with whom he shared the bonding and elation of a successful working party. Sometimes, even if his company succeeds, he is unhappy and unfulfilled.

Problems With Going Small: A Chief Without a Tribe

The opposite occurs when a C.E.O. is recruited from a large company to run a young one. Such people often have no experience with consensus-based groups.

…There is no hierarchical organization; it is a camp. He cannot delegate; he must work by consensus.

Conclusion

The literature and techniques of anthropology and cultural evolution can be used to understand business organizations at different scales. We have explained three familiar failure modes of chief executive officers, derived from studies of primitive societies and their leadership. We have shown that these failure modes can be avoided if the C.E.O. and the company's employees understand and conform to the deep structure of their organization.

We have also shown that the board of directors of a modern corporation is a more primitive and intrinsically different structure from the organization it serves, and that C.E.O.'s must use fundamentally different techniques to work with their boards and with their companies.

Many failures of companies and their C.E.O.'s can be avoided by supplementing graduate business training, … The goal is for the new C.E.O. to have the training to understand the differences between the organization he is entering and the one he is leaving.

In the absence of knowledge, people do the things that have worked for them in the past, and when they fail to work, simply do the same things more intensively, like a tourist in a foreign country who just shouts louder if he is not understood. …

Venture capitalists, executive recruiters and board members of young companies who have a stake in the success of the people they fund or recruit can reduce their risks considerably by discussing consensual organizations with their candidates. …

© 1989, 1990, 1996 Edward F. Tuck and Timothy Earle

(1) L.J. Eaves, H.J. Eysenck and N.G. Martin, "Genes, Culture and Personality: An Empirical Approach" (Academic Press, 1989).

(2) Allen W. Johnson and Timothy Earle, "The Evolution of Human Societies" (Stanford University Press, 1987). This work includes observations on the structure and leadership of primitive polities; insights from this book and the following monograph are used throughout the remainder of this article without specific reference.

(3) Timothy Earle, "Chiefdoms in Archaeological and Ethnohistorical Perspective," from the "Annual Review of Anthropology" (Annual Reviews Inc., 1987).

(4) Andrew Bard Schmookler, "The Parable of the Tribes" (University of California Press, 1984), p. 92. This work, subtitled "The Problem of Power in Social Evolution," contains many strong parallels to modern corporate behavior.

(5) Gregory A. Johnson, "Organizational Structure and Scalar Stress," from "Theory and Explanation in Archaeology," edited by C.A. Renfrew, M.J. Rowlend and D.A. Segraves (Academic Press, 1982), pp. 389-421.

(6) Gregory A. Johnson, op. cit. p. 402.

(7) Niccolò Machiavelli, "The Prince," translated by Luigi Ricci (The New American Library, 1952), p. 116.

(8) Eric Flamholtz, "How to Make the Transition From Entrepreneurship to a Professionally Managed Firm" (Jossey-Bass, 1986).

Illustrations by Bryan Wiggins

Reprint No. 96402

Wednesday, November 10, 2010

Few employers planning to drop health plans after reform is in place, survey finds

Employee Benefit News

By Lydell C. Bridgeford

November 10, 2010

Only six percent of large employers with less than 500 employees report they are likely to drop health coverage after the insurance exchanges go into effect in 2014. That number drops to three percent for employers with 10,000 employees.Image via WikipediaWhether an employer continues to offer health insurance once state-run insurance exchanges take effect in 2014 will largely depend on the size of the employer, according to a survey by Mercer.

Large employers "are reluctant to lose control over a key employee benefit," says Tracy Watts, a partner in Mercer’s Washington, D.C. office.

"But beyond that, once you consider the penalty, the loss of tax savings and grossing up employee income so they can purchase comparable coverage through an exchange, for many employers dropping coverage may not equate to savings," she adds.

Small employers, however, took a different perspective on whether they will provide health coverage in 2014 because of the exchanges. For instance, 20% of businesses with 10 to 499 workers say they’re likely to drop health insurance.

The reason, in part, stems for small businesses gravitating toward fully insured health plans, which makes them vulnerable to large rate increases because of a small risk pools and minimal purchasing power.

The survey represents the responses of more than 2,800 employers. Other key findings from the survey include:Image via Wikipedia"You can see why the idea of dropping employee health plans would be attractive to small employers," especially those with a hight turnover rate and low-paid workforce, says Beth Umland, who directed the study for Mercer. …

- While 17% of employers with 50 or more employees say that the new PPACA requirements generally taking effect for 2011 – extending coverage eligibility to dependents up to age 26 and removing lifetime benefit limits – will have no effect on their cost in 2011, nearly as many (16%) estimate that it will raise cost by 5% or more. Mercer analysts report that PPACA will increase cost by two percent or less.

- When asked about their most likely response to the excise tax, about a fourth of employers with 50 or more employees (23%) say: “We will do whatever is necessary to bring cost below the threshold amounts.”

- An additional 37% of employers say they will attempt to bring the cost below the threshold amounts, but acknowledged that “it may not be possible.”

- Only 3% say they will take no special steps to bring cost below the threshold amounts, and the rest (37%) predict their plans won’t ever hit the cost threshold, which will be tied to CPI and increase each year.

Image via Wikipedia"It’s important to keep in mind that this new tax is still eight years out and a lot could change between now and then," says Watts. "Given how often ERISA, tax, Medicare and Medicaid rules are modified, there’s a good chance that the excise tax that takes effect in 2018 won’t be exactly the same as the sketch we’re working from today," she adds.

Related articles

- Healthcare reform not top U.S. voter issue - poll (reuters.com)

- Insurance Premiums Rise, High-Deductible Plans Increase, Health Costs Can Lead To Elder Bankruptcy (medicalnewstoday.com)

- You: Workers' health insurance costs for 2011 include higher premiums and co-payments (washingtonpost.com)

The ideal DC plan: auto-enrollment, escalator and quicker vesting

Employee Benefit Adviser

Posted November 8, 2010 by Editorial Staff at 10:43AM.

That’s the conclusion of a new study from Northern Trust Global Investments, “The Path Forward: Designing the Ideal Defined Contribution Plan.” Northern Trust surveyed 50 large DC plan sponsors, representing more than 970,000 participants and over $100 billion in plan assets, as well as five leading investment consultants.Image by Getty Images via @daylifeThe ideal defined contribution plan should be mandatory, and include auto-enrollment, savings escalation and employer contributions, sponsors of large retirement plans believe.

The survey found that 63% of plan sponsors and four out of five consultants think participation in DC plans should not be optional. Forty-nine of the 50 plan sponsors and all of the investment consultants believe automatic enrollment should be a key feature of DC plan construction. Currently, federal data indicate that only 19% of private industry workers are enrolled in plans with automatic enrollment, according to Northern Trust.

Seventy-five percent of the plan sponsors and all of the consultants support automatic escalation, which would build on the default level of between 3% and 7% for employee salary contributions to auto-enrollment plans.

Almost all plan sponsors and consultants report that the ideal DC plan structure would include significant contributions from employers, while 60% of plan sponsors believe employer contributions should vest immediately, instead of waiting until an employee works for one year or more at the company.

The majority of those surveyed also said they were in favor of government and employer policies, including tax incentives, restrictions on taking loans against plan balances and transparent fee structures, to strengthen plans.

— By Ruthie Ackerman, an online editor for Financial Planning, a SourceMedia publication.Image via Wikipedia“The study participants describe the ideal DC plan as simple, automatic and cost effective,” says Jim Danaher, senior investment product manager for Defined Contribution Solutions at Northern Trust. “These traits are necessary to satisfy the requirements of three different constituencies: employees who need an efficient means of accumulating assets for retirement; employers in need of a cost-effective benefit to attract and retain valuable employees; and policymakers in need of a reliable savings vehicle in an age of lengthening life spans, pension funding crises, and chronic under-saving.”

Related articles

- Diversified/AHA Survey Reveals that Cost Cutting Measures and Need for Improved Plan Management Drive Retirement Plan Changes (eon.businesswire.com)

- Robust Implementation of Auto Features Key to Improving 401(k) Retirement Savings Says Callan DC Practice Leader (eon.businesswire.com)

- DC Plan Participants Have a Significant Amount of Unmet Needs About Retirement Planning (prnewswire.com)

Tuesday, November 9, 2010

Office Depot survey reveals that saving money and economic issues continue to be at the forefront of small businesses

Employee Benefit News

By WebCPA Staff

November 9, 2010

Attitudes toward the economy have improved over the past month among both small and midsized businesses, according to a new survey.

Significantly more small businesses expect that their firms will be hiring new employees in the next six months (26% in October compared to 19% in September).Image via WikipediaFindings in the latest monthly Office Depot Small Business Index indicate that small business confidence has increased significantly in terms of their overall economic forecast for the next six months, with more businesses anticipating higher company sales, profits and capital spending, while more respondents believe it will be easier to obtain a bank loan as well.

In fact, more respondents across both small and midsized firms (1-5 employees up to 20-99 employees) indicate that they will be adding new employees in the near future compared to findings seen only one month ago.

Moreover, when asked why they'll be hiring, more respondents in the October Small Business Index indicated that their "business is improving" (65% in October vs. 48% in September) and they feel that there is greater “economic certainty/stability” (24% in October vs. 19% in September).

“What we are hearing is that many small businesses are beginning to see a light at the end of the tunnel — unfortunately nobody knows for sure what that light is,” says Office Depot interim chairman and CEO Neil Austrian.

Despite a more positive outlook on the economy as a whole, the vast majority of small businesses surveyed indicate that the current economic environment will have an impact on their holiday gift planning — for both their clients and staff.

Accordingly, less than two-fifths of the respondents plan on buying or sending gifts to their clients this year (38%), with just over half indicating that they will take care of their staff this holiday season (51%).

WebCPA is an online publication of SourceMedia

.

Related articles

- Small Business Believes New Congress Means Business Will Improve (eon.businesswire.com)

- Small-Business Index in U.S. Rises to Highest in Five Months (businessweek.com)

- Fed survey: new standards don't lure small firms (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

Labels:

Business Planning,

Human Resources,

Talent Retention

More Workers Staying Put During Economic Uncertainty

November 8, 2010 (PLANSPONSOR.com) - All three generations in today’s workforce are exhibiting a decreased propensity for change, according to the 2010/2011 PwC Saratoga U.S. Human Capital Effectiveness Report.

The report said one key measure PwC Saratoga uses to measure quality of hire is turnover in the first year of service. After climbing in the two years prior to the recession, turnover rates in the first year of service are down by 16% since 2008. In 2009, less than one in four employees departed within the first year of service (compared to nearly one in three in 2007).Image via WikipediaAn executive summary of the report says voluntary separation rates across the three generations continue to decrease, with steady declines among Baby Boomers, Generation X, and Generation Y since 2007. Baby Boomers continued to voluntarily leave the workforce at the lowest rate among the three groups - just 4.9% in 2009, compared with 5.9% for Generation X and 10.9% for Generation Y. The Baby Boomer voluntary separation rate has decreased 18% since 2007. …

While employee compensation costs per full-time employee (FTE) remained flat between 2008 and 2009, the recession had a direct bearing on performance bonuses. The percentage of employee compensation made up of performance bonus pay has declined 55% in the past three years, from 8.8% of salary in 2007 to 4% in 2009. The past year alone saw a decrease of 44%, from 7.2% to 4%.

PwC Saratoga found increases in the cost of employee health care. Health care costs per active employee increased nearly 6% between 2008 and 2009 to an average of $8,335. While costs are increasing, the share of health care costs borne by employers has decreased by nearly 2% between 2008 and 2009 with employers responsible for 79.7% of health care costs.

After rising every year since 2005, workforce productivity fell in 2009. Revenue per FTE dropped 6%, from a high of $413,690 in 2008 to $387,993 in 2009. Nevertheless, 2009 results are 18% higher than 2006 results of $330,060.

Human capital return on investment (ROI), a key indicator of return on workforce investment, is down 23% to 43 cents in profit for every dollar invested in the workforce compared with the 2007 and 2008 result of 53 cents in profit for every dollar invested in the workforce. Additionally, PwC Saratoga results show that organizations have increased their investment in workforce compensation and benefit costs for each dollar of revenue generated. In 2008, organizations invested $221 for every $1,000 in revenue. In 2009, organizations invested $259 for every $1,000 in revenue.

The report includes data from nearly 300 organizations representing 12 industry sectors that provided information from the 2009 calendar year. The average company in the report has annual revenue of $5.7 billion and more than 19,000 employees.

Rebecca Moore

editors@plansponsor.com

Related articles

- Motivating a Changing Workforce (thinkup.waldenu.edu)

- Baby Boomers Become the New Employee, Again (workplaceculture.suite101.com)

- Employees May Have No More to Give as Engagement Makes Modest Gains in the U.S. Workforce (prweb.com)

Monday, November 8, 2010

The CEO's guide to corporate finance

Four principles can help you make great financial decisions—even when the CFO’s not in the room.

McKinsey Quarterly

NOVEMBER 2010 • Richard Dobbs, Bill Huyett, and Tim Koller

It’s one thing for a CFO to understand the technical methods of valuation—and for members of the finance organization to apply them to help line managers monitor and improve company performance. But it’s still more powerful when CEOs, board members, and other nonfinancial executives internalize the principles of value creation. Doing so allows them to make independent, courageous, and even unpopular business decisions in the face of myths and misconceptions about what creates value.

When an organization’s senior leaders have a strong financial compass, it’s easier for them to resist the siren songs of financial engineering, excessive leverage, and the idea (common during boom times) that somehow the established rules of economics no longer apply. …

What we hope to do in this article is show how four principles, or cornerstones, can help senior executives and board members make some of their most important decisions. The four cornerstones are disarmingly simple:

1. The core-of-value principle establishes that value creation is a function of returns on capital and growth, while highlighting some important subtleties associated with applying these concepts.

2. The conservation-of-value principle says that it doesn’t matter how you slice the financial pie with financial engineering, share repurchases, or acquisitions; only improving cash flows will create value.

3. The expectations treadmill principle explains how movements in a company’s share price reflect changes in the stock market’s expectations about performance, not just the company’s actual performance (in terms of growth and returns on invested capital). …

4. The best-owner principle states that no business has an inherent value in and of itself; it has a different value to different owners or potential owners—a value based on how they manage it and what strategy they pursue.

View these principles and their implications at a glance.

Ignoring these cornerstones can lead to poor decisions that erode the value of companies. Consider what happened during the run-up to the financial crisis that began in 2007. Participants in the securitized-mortgage market all assumed that securitizing risky home loans made them more valuable because it reduced the risk of the assets. …Securitization did not increase the aggregated cash flows of the home loans, so no value was created, and the initial risks remained. Securitizing the assets simply enabled the risks to be passed on to other owners: …

Obvious as this seems in hindsight, a great many smart people missed it at the time. …

Mergers and acquisitions

Acquisitions are both an important source of growth for companies and an important element of a dynamic economy. Acquisitions that put companies in the hands of better owners or managers or that reduce excess capacity typically create substantial value both for the economy as a whole and for investors.

… But although they create value overall, the distribution of that value tends to be lopsided, accruing primarily to the selling companies’ shareholders. In fact, most empirical research shows that just half of the acquiring companies create value for their own shareholders.

The conservation-of-value principle is an excellent reality check for executives who want to make sure their acquisitions create value for their shareholders. The principle reminds us that acquisitions create value when the cash flows of the combined companies are greater than they would otherwise have been. Some of that value will accrue to the acquirer’s shareholders if it doesn’t pay too much for the acquisition.

Exhibit 1 shows how this process works. Company A buys Company B for $1.3 billion—a transaction that includes a 30 percent premium over its market value. Company A expects to increase the value of Company B by 40 percent through various operating improvements, so the value of Company B to Company A is $1.4 billion. Subtracting the purchase price of $1.3 billion from $1.4 billion leaves $100 million of value creation for Company A’s shareholders.

Exhibit 1: To create value, an acquirer must achieve performance improvements that are greater than the premium paid.

In other words, when the stand-alone value of the target equals the market value, the acquirer creates value for its shareholders only when the value of improvements is greater than the premium paid. …

While a 30 or 40 percent performance improvement sounds steep, that’s what acquirers often achieve. For example, Exhibit 2 highlights four large deals in the consumer products sector. Performance improvements typically exceeded 50 percent of the target’s value.

Exhibit 2: Dramatic performance improvement created significant value in these four acquisitions. Our example also shows why it’s difficult for an acquirer to create a substantial amount of value from acquisitions. Let’s assume that Company A was worth about three times Company B at the time of the acquisition. Significant as such a deal would be, it’s likely to increase Company A’s value by only 3 percent—the $100 million of value creation depicted in Exhibit 1, divided by Company A’s value, $3 billion.

Finally, it’s worth noting that we have not mentioned an acquisition’s effect on earnings per share (EPS). Although this metric is often considered, no empirical link shows that expected EPS accretion or dilution is an important indicator of whether an acquisition will create or destroy value. …To avoid confusion during such communications, executives should remind themselves and their colleagues that EPS has nothing to say about which company is the best owner of specific corporate assets or about how merging two entities will change the cash flows they generate.

Divestitures

Executives are often concerned that divestitures will look like an admission of failure, make their company smaller, and reduce its stock market value. Yet the research shows that, on the contrary, the stock market consistently reacts positively to divestiture announcements.1 The divested business units also benefit. Research has shown that the profit margins of spun-off businesses tend to increase by one-third during the three years after the transactions are complete.2

These findings illustrate the benefit of continually applying the best-owner principle: … At different stages of an industry’s or company’s lifespan, resource decisions that once made economic sense can become problematic. …

A value-creating approach to divestitures can lead to the pruning of good and bad businesses at any stage of their life cycles. … One way to do so is to hold regular review meetings specifically devoted to business exits, ensuring that the topic remains on the executive agenda and that each unit receives a date stamp, or estimated time of exit. This practice has the advantage of obliging executives to evaluate all businesses as the “sell-by date” approaches.

Executives and boards often worry that divestitures will reduce their company’s size and thus cut its value in the capital markets. … But this notion holds only for very small firms, with some evidence that companies with a market capitalization of less than $500 million might have slightly higher costs of capital.3

Finally, executives shouldn’t worry that a divestiture will dilute EPS multiples. A company selling a business with a lower P/E ratio than that of its remaining businesses will see an overall reduction in earnings per share. … With this unit gone, the company that remains will have a higher growth and ROIC potential—and will be valued at a correspondingly higher P/E ratio.4 As the core-of-value principle would predict, financial mechanics, on their own, do not create or destroy value. By the way, the math works out regardless of whether the proceeds from a sale are used to pay down debt or to repurchase shares. What matters for value is the business logic of the divestiture.

Project analysis and downside risks

Reviewing the financial attractiveness of project proposals is a common task for senior executives. … For example, one company we know analyzed projects by using advanced statistical techniques that always showed a zero probability of a project with negative net present value (NPV). …

Such an approach ignores the core-of-value principle’s laserlike focus on the future cash flows underlying returns on capital and growth, not just for a project but for the enterprise as a whole. Actively considering downside risks to future cash flows for both is a crucial subtlety of project analysis—and one that often isn’t undertaken.

For a moment, put yourself in the mind of an executive deciding whether to undertake a project with an upside of $80 million, a downside of –$20 million, and an expected value of $60 million. Generally accepted finance theory says that companies should take on all projects with a positive expected value, regardless of the upside-versus-downside risk.

But what if the downside would bankrupt the company? That might be the case for an electric-power utility considering the construction of a nuclear facility for $15 billion … Suppose there is an 80 percent chance the plant will be successfully constructed, … and worth, net of investment costs, $13 billion. Suppose further that there is also a 20 percent chance that the utility company will fail to receive regulatory approval to start operating the new facility, which will then be worth –$15 billion. That means the net expected value of the facility is more than $7 billion—seemingly an attractive investment.5

The decision gets more complicated if the cash flow from the company’s existing plants will be insufficient to cover its existing debt plus the debt on the new plant if it fails. … Failure will wipe out all the company’s equity, not just the $15 billion invested in the plant.

As this example makes clear, we can extend the core-of-value principle to say that a company should not take on a risk that will put its future cash flows in danger. … On the other hand, if the project doesn’t endanger the company, they should be willing to risk the … loss for a far greater potential gain.

Executive compensation

Establishing performance-based compensation systems is a daunting task, …[Many] companies continue to reward [executives] for short-term total returns to shareholders (TRS). TRS, however, is driven more by movements in a company’s industry and in the broader market (or by stock market expectations) than by individual performance. …

Using TRS as the basis of executive compensation reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of the third cornerstone of finance: the expectations treadmill. If investors have low expectations for a company at the beginning of a period of stock market growth, it may be relatively easy for the company’s managers to beat them. But that also increases the expectations of new shareholders, so the company has to improve ever faster just to keep up and maintain its new stock price. At some point, it becomes difficult if not impossible for managers to deliver on these accelerating expectations without faltering, much as anyone would eventually stumble on a treadmill that kept getting faster.

This dynamic underscores why it’s difficult to use TRS as a performance-measurement tool: extraordinary managers may deliver only ordinary TRS because it is extremely difficult to keep beating ever-higher share price expectations. Conversely, if markets have low performance expectations for a company, its managers might find it easy to earn a high TRS, at least for a short time, by raising market expectations up to the level for its peers.

Instead, compensation programs should focus on growth, returns on capital, and TRS performance, relative to peers (an important point) rather than an absolute target. That approach would eliminate much of the TRS that is not driven by company-specific performance. Such a solution sounds simple but, until recently, was made impractical by accounting rules and, in some countries, tax policies. …

Since 2004, a few companies have moved to share-based compensation systems tied to relative performance. GE, for one, granted its CEO a performance award based on the company’s TRS relative to the TRS of the S&P 500 index. We hope that more companies will follow this direction.

Applying the four cornerstones of finance sometimes means going against the crowd. … None of this is easy, but the payoff—the creation of value for a company’s stakeholders and for society at large—is enormous.

In a new book, Value: The Four Cornerstones of Corporate Finance, McKinsey’s Richard Dobbs, Bill Huyett, and Tim Koller show the power of four disarmingly simple but often-ignored financial principles. Here are some practical applications.

Exhibit 3: Four cornerstones of value creation at a glance

About the Authors

Richard Dobbs is a director in McKinsey’s Seoul office and a director of the McKinsey Global Institute; Bill Huyett is a director in the Boston office; and Tim Koller is a principal in the New York office. This article has been excerpted from Value: The Four Cornerstones of Corporate Finance, by Richard Dobbs, Bill Huyett, and Tim Koller (Wiley, October 2010). Koller is also a coauthor of Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies, (fifth edition, Wiley, July 2010). To learn more about both books, please visit our information page on the McKinsey & Company Web site.

Notes

1 J. Mulherin and Audra Boone, “Comparing acquisitions and divestitures,” Journal of Corporate Finance, 2000, Volume 6, Number 2, pp. 117–39.

2 Patrick Cusatis, James Miles, and J. Woolridge, “Some new evidence that spinoffs create value,” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 1994, Volume 7, Number 2, pp. 100–107.

3 See Robert S. McNish and Michael W. Palys, “Does scale matter to capital markets?” mckinseyquarterly.com, June, 2005.

4 Similarly, if a company sells a unit with a high P/E relative to its other units, the earnings per share (EPS) will increase but the P/E will decline proportionately.

5 The expected value is $7.4 billion, which represents the sum of 80 percent of $13 billion ($28 billion, the expected value of the plant, less the $15 billion investment) and 20 percent of –$15 billion ($0, less the $15 billion investment).

Related articles

- Proformative Seminar Series: "M&A for CFOs: What You Don't Know Might Kill (Your Deal)" (prweb.com)

- A Simple Guide to the Process of Corporate Divestitures (strategic-business-planning.suite101.com)

Wednesday, November 3, 2010

Unless the Bush tax cuts are extended, more money will be withheld from employees paychecks on Jan. 1, 2011

Employee Benefit Adviser

By Editorial Staff

November 1, 2010

“Ten years ago, we were facing the same situation: There was talk of upcoming tax cuts,” says John W. Strzelecki, CCH senior payroll analyst. The tax cuts – now known as the “Bush tax cuts” – were signed on June 7, 2001. The IRS subsequently issued new withholding tables, effective July 1, 2001, that incorporated the new tax cuts….Image via WikipediaUnless the lame-duck Congress acts to extend the Bush-era tax cuts about to expire at the end of 2010, the income tax rates that will take effect Jan. 1, 2011 will return to the rates that were in effect a decade ago. The result: More money will be withheld from paychecks, according to an analyst at the tax publisher CCH.

Strzelecki says the IRS will likely issue new withholding tables sometime this month effective Jan. 1, 2011, based on the 2001 tax rates that are scheduled to go into effect at the start of the year. In addition, the IRS will incorporate the 2011 personal exemption amount —projected to be $3,700 …Image via WikipediaFast forward to today. The Bush tax cuts are nearing expiration at the end of the year. Under federal law, the tax rates that will be in effect Jan. 1, 2011, will be the rates that were in effect on Jan. 1, 2001.

What happens if the Bush tax cuts are extended? According to Strzelecki, the IRS will revise the withholding tables with an effective date that allows just enough time for the payroll industry to implement the changes, as they did in June 2001. The tables will take into account the fact that too much money was withheld from the paychecks that were issued prior to the tax cuts. …

“What it all boils down to is workers will see less take home pay beginning in 2011 …,” says Strzelecki.

Related articles

- Priority One for Republicans: Extend the Bush Tax Cuts (newsbusters.org)

- Bush Tax Cuts Future Up To Obama (huffingtonpost.com)

- Lengthy to-do list awaits lame duck session (sfgate.com)

QE2 and the Great Wealth Transfer: A Spurt for the Economy?: Searching for Alpha

Advisor One

November 2, 2010 | By Ben Warwick

November 2, 2010 | By Ben Warwick

Quantitative easing (QE) is a government strategy of printing money in order to retire debt and purchase assets that increase the size of the public balance sheet. QE1, which occurred in March 2009, effectively took the markets off the mat. QE2 will likely also light a fire under stock prices, but the effect may be short-lived.

Since the assets purchased are all debt-related, there is little doubt that interest rates will stay low or even head slightly lower. Corporations will continue to sell bonds in this environment, which will increase their cash hordes even more. As more firms start distributing this cash in the form of dividends, investors will turn their eyes away from the negligible return of CDs and Treasury notes and toward the stock market.

Not everyone will win in the next upswing. The battered middle class, who is already cash strapped and struggling with high unemployment, won’t have the wherewithal to participate in the rally. This will serve to separate them from the upper class even more—a vexing long-term problem that we will eventually have to deal with.Image via WikipediaThe economy should respond to such stimulus, but not with the vigor of the public markets. If GDP growth doesn’t get a sufficient boost, investors will begin to focus on the falling dollar and rising government debt levels. Although I’m still expecting a rally, it may be in the form of a powerful spurt rather than a long-term trend.

Ben Warwick is CIO of Memphis-based Sovereign Wealth Management. He can be reached atmailto:puzzler@investmentadvisor.com.

About the Author

Ben Warwick

Contributing Editor

Related articles

- Q&A on QE2: What a Fed Move Would Mean (blogs.wsj.com)

- US Federal Reserve's latest bubble threatens mayhem (telegraph.co.uk)

- Here's Everything You Need To Know Ahead Of The Fed's Big Decision On Quantitative Easing (businessinsider.com)

Labels:

Business Planning,

Decision making,

Investing,

Loan,

Public sector

Monday, November 1, 2010

Larger Withdrawals From IRAs in 2010 May Help Savers With Taxes

Bloomberg

By Danielle Kucera - Oct 20, 2010 11:01 PM CT

For U.S. taxpayers making mandatory withdrawals from an individual retirement account, 2010 may be a good year to take out more than necessary because tax rates may rise. …

Savers who may be in a higher tax bracket next year should consider withdrawing more than the minimum in 2010, said Mark Nash, a partner in the Dallas office of the New York-based Private Company Services practice of accounting and advisory firm PwC. Required withdrawals are based on a formula of the account balance and the individual’s age.

“Pulling out a large sum in 2010 would lessen the 2011 amount, and make that year’s distribution lower,” said Nash, who advises high net-worth investors. …

The U.S. government suspended required minimum distributions for tax year 2009 in response to plummeting account balances after the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index dropped 38 percent in 2008. Mandatory distributions returned in 2010 as the economy strengthened and the S&P 500 rose 23 percent in 2009. Roth IRAs, which are funded with post-tax dollars, are exempt from minimum withdrawal rules while the owner is alive.

Rising Rates

President Barack Obama has proposed allowing the top two marginal income tax rates to rise to 39.6 percent and 36 percent from 35 percent and 33 percent for individuals earning more than $200,000 and couples making more than $250,000. Congress is scheduled to take up taxes when it returns from recess in November.

“This uncertainty doesn’t mean that people shouldn’t be sitting down and doing their planning now,” said Greg Rosica, a tax partner at consulting firm Ernst & Young LLP in Tampa, Florida, and contributing author to the Ernst & Young Tax Guide.

Someone who may be in a lower tax bracket in 2010 because of large deductions or less income should also consider taking a bigger distribution this year to take advantage of lower rates, said Rebecca Pavese, an accountant at Palisades Hudson Financial Group’s national tax practice in Atlanta.

Combine Withdrawals

Taxpayers who aren’t already taxed at top rates should make sure taking a bigger distribution won’t tip them into a higher bracket, said Bill Fleming, a managing director in the Hartford, Connecticut, office of PwC. …

Those who pay estimated taxes during the year can request the account administrator to withhold money from their RMDs and pay income tax just once at the year’s end, said Rosica of Ernst & Young. That way they can hold onto their money longer and invest it without paying a penalty for underpayment, Pavese said.

The law assumes that payments are made equally throughout the year unless the taxpayer states otherwise, according to the IRS.

Charity Deduction

… Any IRA account holder can give all or part of a distribution to charity and take a deduction for the donation, said Debbie Cox, a Dallas, Texas-based wealth adviser for J.P. Morgan Private Bank, which is based in New York. A provision that allowed taxpayers to roll over a distribution directly to a charity and avoid income tax expired at the end of 2009, she said.

IRA holders should also try to take their required withdrawals at roughly the same time every year to avoid mistakes or forgetting about it, Fleming, of PwC, said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Danielle Kucera in New York at dkucera6@bloomberg.net.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rick Levinson at rlevinson2@bloomberg.net.

Related articles

- Taxes 101: IRA Conversions (turbotax.intuit.com)

- 60 Days from Today: Tsunami of Tax Hikes on Horizon After Election Day (prnewswire.com)

- You: Stock sales will soon bring new tax twist (menafn.com)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)