Procedures for estimating a company’s future cash flows discounted at a rate that reflects risk are the same everywhere. But in emerging markets, the risks are much greater.

McKinsey QuarterlyDECEMBER 2000 • Mimi James and Timothy M. Koller

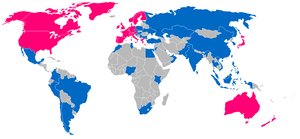

As the economies of the world globalize and capital becomes more mobile, valuation is gaining importance in emerging markets—for privatization, joint ventures, mergers and acquisitions, restructuring, and just for the basic task of running businesses to create value. Yet valuation is much more difficult in these environments because buyers and sellers face greater risks and obstacles than they do in developed markets.

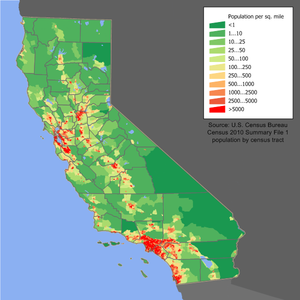

In recent years, nowhere have those risks and obstacles been more serious than in the emerging markets of East Asia. … In Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, South Korea, and Thailand—the hardest-hit Asian economies—cross-border majority-owned M&A reached an annual average value of $12 billion in both 1998 and 1999, compared with $1 billion annually from 1994 to 1996.1

Image via WikipediaYet little agreement has emerged among academics, investment bankers, and industry practitioners about how to conduct valuations in emerging markets. … Our preferred approach is to use discounted cash flows (DCFs) together with probability-weighted scenarios that model the risks a business faces.2

Image via WikipediaYet little agreement has emerged among academics, investment bankers, and industry practitioners about how to conduct valuations in emerging markets. … Our preferred approach is to use discounted cash flows (DCFs) together with probability-weighted scenarios that model the risks a business faces.2Macroeconomic volatility is another minefield in Asia, where the financial collapse and subsequent recession generated a mountain of nonperforming bank loans. …

A simple risk premium isn’t enough

Image via WikipediaIn valuations based on discounted cash flows, two options are available for incorporating the additional risks of emerging markets. Those risks can be included either in the assessment of the actual cash flow (the numerator in a DCF calculation) or in an extra risk premium added to the discount rate (the denominator)—the rate used to calculate the present value of future cash flows. We believe that accounting for these risks in the cash flows through probability-weighted scenarios provides both a more solid analytical foundation and a more robust understanding of how value might (or might not) be created. Three practical arguments support our point of view.

Image via WikipediaIn valuations based on discounted cash flows, two options are available for incorporating the additional risks of emerging markets. Those risks can be included either in the assessment of the actual cash flow (the numerator in a DCF calculation) or in an extra risk premium added to the discount rate (the denominator)—the rate used to calculate the present value of future cash flows. We believe that accounting for these risks in the cash flows through probability-weighted scenarios provides both a more solid analytical foundation and a more robust understanding of how value might (or might not) be created. Three practical arguments support our point of view.Second, many risks in a country are idiosyncratic: they don’t apply equally to all industries or even to all companies within an industry. The common approach to building additional risk into the discount rate involves adding to it a country risk premium equal to the difference between the interest rate on a local bond denominated in US dollars and a US government bond of similar maturity. But this method clearly doesn’t take into account the different risks that different industries face; …

Third, using the credit risk of a country as a proxy for the risk faced by corporations overlooks the fact that equity investments in a company can often be less risky than investments in government bonds. …

In principle, equity markets might be expected to factor in a sizable country risk measure when automatically valuing companies in emerging markets. But equity markets don’t really do so—at least not consistently. …

…(Exhibit 1). Although not definitive proof that no country risk premium is factored into the stock market valuations of companies in emerging markets, this finding clearly suggests that market prices for equities don’t take account of the commonly expected country risk premium. If these premiums were included in the cost of capital, the valuations would be 50 to 90 percent lower than the market values.

Incorporating risks in cash flows

Overall, our approach to valuation helps managers achieve a much better understanding of explicit risks and their effect on cash flows than does the simple country-risk-premium method.Analyzing specific risks and their impact on value helps managers make better plans to mitigate them. …

To incorporate risks into cash flows properly, start by using macroeconomic factors to construct scenarios, because such factors affect the performance of industries and companies in emerging markets. Then align specific scenarios for companies and industries with those macroeconomic scenarios. … Since values in emerging markets are often more volatile, we recommend developing several scenarios.

Image via WikipediaThe major macroeconomic variables that have to be forecast are inflation rates, growth in the gross domestic product, foreign-exchange rates, and, often, interest rates. … When constructing a high-inflation scenario, be sure that foreign-exchange rates reflect inflation in the long run, because of purchasing-power parity.5 Next, determine how changes in macroeconomic variables drive each component of the cash flow. Cash flow items likely to be affected are revenue, expenses, working capital, capital spending, and debt instruments. These should then be linked in the model to the macroeconomic variables so that when the macroeconomic scenario changes, cash flow items adjust automatically.

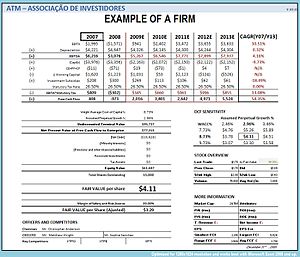

Image via WikipediaThe major macroeconomic variables that have to be forecast are inflation rates, growth in the gross domestic product, foreign-exchange rates, and, often, interest rates. … When constructing a high-inflation scenario, be sure that foreign-exchange rates reflect inflation in the long run, because of purchasing-power parity.5 Next, determine how changes in macroeconomic variables drive each component of the cash flow. Cash flow items likely to be affected are revenue, expenses, working capital, capital spending, and debt instruments. These should then be linked in the model to the macroeconomic variables so that when the macroeconomic scenario changes, cash flow items adjust automatically.We used this approach in a 1998 outside-in valuation of Pão de Açúcar, a Brazilian retail-grocery chain. The forecasts were developed with the help of three macroeconomic scenarios published by an investment bank, Merrill Lynch (Exhibit 2). Our first scenario, or base case, assumed that Brazil would enact fiscal reforms and enjoy continued international support and that the country’s economy could therefore recover fairly quickly from the shock waves of the Asian economic crisis. … The second scenario assumed that Brazil’s economy would remain in recession for two years, with high interest rates and low GDP growth and inflation. The third scenario assumed a dramatic devaluation—which is what actually happened. In this third scenario, inflation would rise to 30 percent and the economy would shrink by 5 percent.

These three macroeconomic scenarios were then incorporated into the company’s cash flows and discounted at an industry-specific cost of capital. The cost of capital also had to be adjusted for Pão de Açúcar’s capital structure and for the difference between the Brazilian and US inflation rates. Next, each outcome was weighted for probability. Exhibit 3 shows the results of the three scenarios and the probability-weighted values. The base case received a probability of between 33 percent and 50 percent; the others were assigned lower probabilities based on our internal assessments. The DCF value range—a large one because of the uncertainties of the times—was about 223 percent to 135 percent of the base case.

The resulting value was $1.026 billion to $1.094 billion, which was within 10 percent of the company’s market value at the time. If we employ the alternative valuation method, using base-case cash flows but adjusting for additional risk by adding Brazil’s country risk premium to the discount rate, we find a value of $221 million—far below the market value.6

Using probability-weighted scenarios brings us much closer to market values and, we believe, to a more accurate view of a company’s true value. Moreover, these scenarios don’t just confirm the market’s valuation of companies; by pinpointing specific risks, they also help managers make the right decisions for those companies.

About the Authors

Mimi James is an alumnus of McKinsey’s New York office, where Tim Koller is a principal. This article is adapted from Tom Copeland, Tim Koller, and Jack Murrin, Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies, third edition, New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2000 (updated to a 5th edition in July 2010, by Marc Goedhart, Tim Koller, and David Wessels).The authors acknowledge the contributions of Cuong Do, Keiko Honda, Takeshi Ishiga, Jean-Marc Poullet, and Duncan Woods to this article.

Notes

1Asian Development Outlook 2000, Asian Development Bank and Oxford University Press, p. 32.2The use of probability-weighted scenarios constitutes an acknowledgment that forecasts of financial performance are at best educated guesses and that the forecaster can do no more than narrow the range of likely future performance levels. Developing scenarios involves creating a comprehensive set of assumptions about how the future may evolve and how it is likely to affect an industry’s profitability and financial performance. Each scenario then receives a weight reflecting the likelihood that it will actually occur. Managers base these estimates on both knowledge and instinct.

3Diversifiable risks are those that could potentially be eliminated by diversification because they are peculiar to a company. Nondiversifiable risks can’t be avoided, because they are derived from broader economic trends. Many practitioners use the capital asset-pricing model (CAPM), developed in the mid-1960s by John Lintner, William Sharpe, and Jack Treynor, to determine the cost of capital. In CAPM, only nondiversifiable risks are relevant. Diversifiable risks would not affect the expected rate of return.

4Tom Keck, Eric Levengood, and Al Longfield, "Using discounted cash flow analysis in an international setting: a survey of issues in modeling the cost of capital," Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, Volume 11, Number 3, fall 1998.

5The theory of purchasing-power parity states that exchange rates should adjust over time so that the prices of goods in any two countries are roughly equal. A Big Mac at McDonald’s, for instance, should cost roughly the same amount in both. In reality, purchasing-power parity holds true over long periods of time, but exchange rates can deviate from it by up to 20 or 30 percent for five to ten years.

6The country risk premium typically used at the time of the valuation (September 1998) was about 8 percent.